The vaccination campaign against COVID in Argentina had irregularities since its inception. Less than two months after it began, a corruption scandal known as the “VIP vaccination centre” came to light: government officials, family members and those closest to the government had received doses before the prioritized groups.

At LA NACION, we decided to follow the campaign and the vaccination system from two different points of view. On the one hand, follow and control the number of doses received, distributed and applied. On the other hand, monitor the implementation of public policies by combining public data and many requests for access to public information as main sources.

What was the impact of the project?

Even though the lack of transparency from the Ministry of Health, LA NACION published many different investigation pieces revealing several inconsistencies in the discourse of public officials and reality: we exposed the path of vaccines so that different officials and close relatives could receive a vaccine before it was due and the application of doses that had already expired or that corresponded to another laboratory different from the one informed to people. This investigation caused great commotion. In particular, the investigation that revealed the path of the VIP vaccine doses was used in the court case that began after this fact became known.

Moreover, a government admitted having committed “involuntary errors” in the application of vaccines after publishing the news story that showed that more than eleven thousand doses had been administered from a laboratory different from the lab administering the initial dose and the one appearing on the vaccine card.

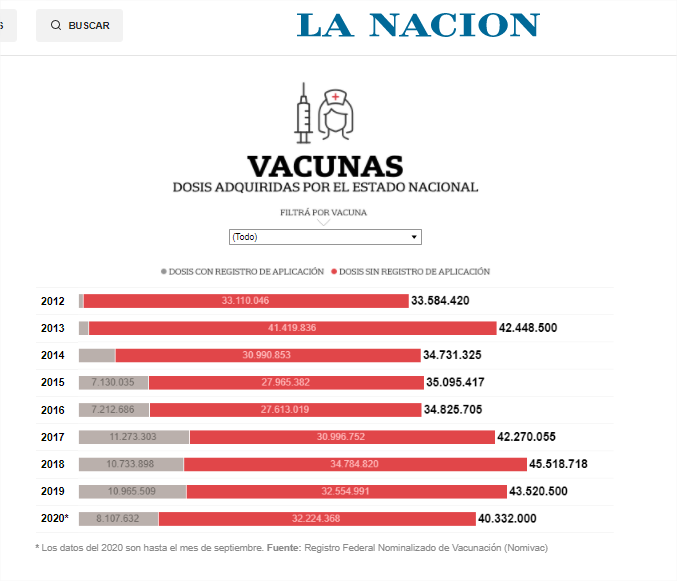

In turn, we decided to investigate the background of the vaccination system in which the COVID immunization campaign was to be planned. We found that in Argentina, due to a lack of integration of the computer systems of the provinces, it is not possible to know how many people were administered a vaccine.

This number is calculated from the number of doses distributed by the National Ministry of Health. Thanks to this news story, government agencies, researchers and civil society in general were able to have access for the first time to the records of the application of calendar vaccines since 2009.

In addition, it was also important for LA NACION to add value by making unique projections and analysis such as an end on vaccination projection on each district, taking into account the rhythm of dose application on each jurisdiction as parametre –with public databases and data from FOIA requests.

What tools, techniques, technologies did you use, and how did you use them?

Approximately twenty persons worked on this project among different productions selected for this category.

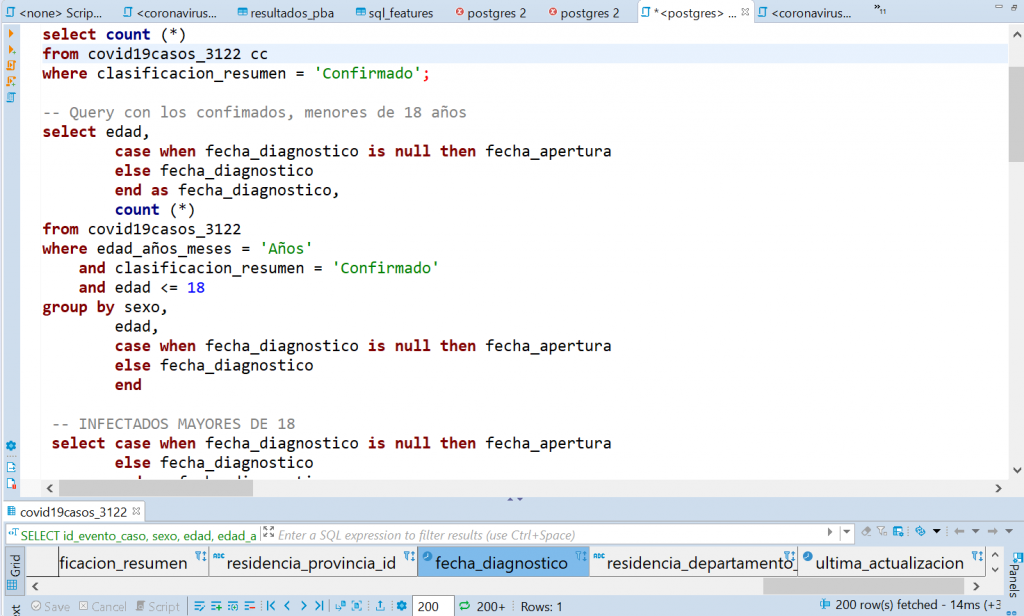

The information process was made in Python and Amazon Web Services (AWS) were used for hosting and deployment of different processes and databases. Visualizations were performed in Vue.js, Chart.js and Canvas.

The project is divided into two large datasets. One of them is designed for world data and the other one is for data from Argentina where there is more fine detail of each dose applied.

For world processing, Our World in Data is taken as source, data are daily downloaded from the source, processed and persisted in a database in Postgres to later make them available and publish them in different infographics.

As regards the Argentina dataset, a file provided by the National Ministry of Health is used as source and it contains data about each application, type of dose, laboratory, age range, among others.

In order to process and persist the files, standardized data of each province, municipality and laboratory are taken into account, so that consistency among all the tables of the COVID project can be maintained.

It was developed an algorithm that reads data from the database on a daily basis, reprocesses it and writes a JSON format file to make data available for the different FrontEnd/Infographics applications. Finally, there is a last process, which takes the data offered by another official source, the Public Immunization Monitor (Monitor Público de Vacunación) and keeps the application totals updated as this source has more frequent updating.

What was the hardest part of this project? What should the jury know to better understand what you did and why it should be selected?

There were many challenges. First of all, how to obtain data. Basic information such as, for example, the exact number of vaccines received, which batches, their origin and to which provinces and agencies they were distributed, can only be accessed through requests for access to public information.

On this regard, the only agency authorized to purchase vaccines in Argentina is the National Ministry of Health and it is very reluctant to share data.

Second, although there is a public database, data cannot be cross-referenced because there are no case IDs and this makes analysis difficult. Data such as, for example, how many people combined vaccines (in Argentina, citizens cannot opt for the vaccine of the laboratory of their choice and many persons were administered their first dose of one brand and the second dose of another one). Although the State has data related to those persons infected by COVID, it is not either possible to cross-reference these data, since the State refuse to publish data in a way that can be related.

Then, even though we decided to connect with the Communication Department of the Ministry of Health during the pandemic, there were many changes in personnel, and despite our repeated requests, we were never able to talk to someone with a technical profile.

Finally, we also made best efforts to understand the national vaccine registry process, but information is not clear, is not very modern, it differs between provinces and due to bureaucracy, there is a long delay in data publication and this circumstance made us face the challenge, in many occasions, of working with outdated information.

What can other journalists learn from this project?

But, despite being very hard to find and have structured, updated, accurate and reliable public records, we were able to find ways to obtain and work with them. This involved strong interdisciplinary work between programmers, specialized journalists, data analysts and data scientists and multimedia designers.

We faced the challenge of working with databases without any case IDs and thus we learned to be creative and find ways to analyze data as well. Also, as the open data files increased with the vaccination record, more team members were needed to analyze it in order to respond to the multiple requests from LA NACION journalists, so they were trained to improve their technical and big data analysis skills to help the rest of the team.

At the same time, it was very important to cross-check official data with requests for access to public information and find ways to improve all the information. This was key to firstly gain access to exclusive data and to be able to move forward with investigation pieces that were not possible due to the reluctance to open data. A fundamental aspect to take into consideration was not to take anything for granted and question the numbers in order to find more and better stories.